When lies cost lives. Economically Motivated Adulteration in the food industry.

The headline of the recent article posted on the BBC News webpage was “Food fraud probe into beef falsely labeled as British”. The issue reported was that the National Food Crime Unit is investigating potential food fraud involving pre-packed sliced beef and deli products that were packaged back to 2021 as if from the UK but in fact, produced in Europe and South America. The fact was that the list of food fraud scandals just came bigger.

Food fraud, also known as Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA), is the act of intentionally altering, misrepresenting, mislabeling, substituting, or tampering with any food product at any point along the farm-to-table food supply chain, for financial advantage. Food adulteration can be done in a number of ways including:

- Labeling non-compliance

- Falsified certifications/documents

- Counterfeiting

- Adulteration

- Substitution

- Use of prohibited treatment and/or process

- Use of prohibited substances

- Use of prohibited products for human consumption

Food fraud isn’t a new issue. In 1970, wheat gluten in flour imported into the US was contaminated with urea as a cheap substitute for protein. In the UK, advertised spicy beef was found to contain undeclared horse meat, which made headline news across Europe, back in 2013. Even though the aim of EMA is not to harm people but to inflate profits, numerous cases that EMA had serious consequences for public health, resulting in severe foodborne illnesses. Rapeseed cooking oil with 2% aniline sold as olive oil caused an outbreak of a condition, known as toxic oil syndrome, in over 200,000 people across Spain in 1981. Three hundred victims died. Melamine adulteration of dairy products in 2008 resulted in 300,000 illnesses, 50,000 hospitalizations, and 6 known infant deaths in China.

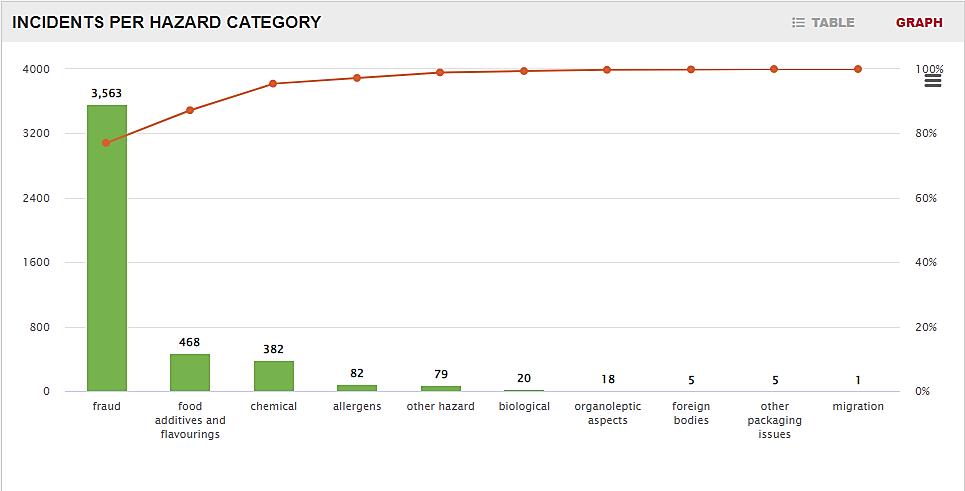

Three thousand fifty hundred and sixty-three incidents of EMA were discovered and reported by authorities, worldwide, for the year 2022 as shown in the following Graph 1.

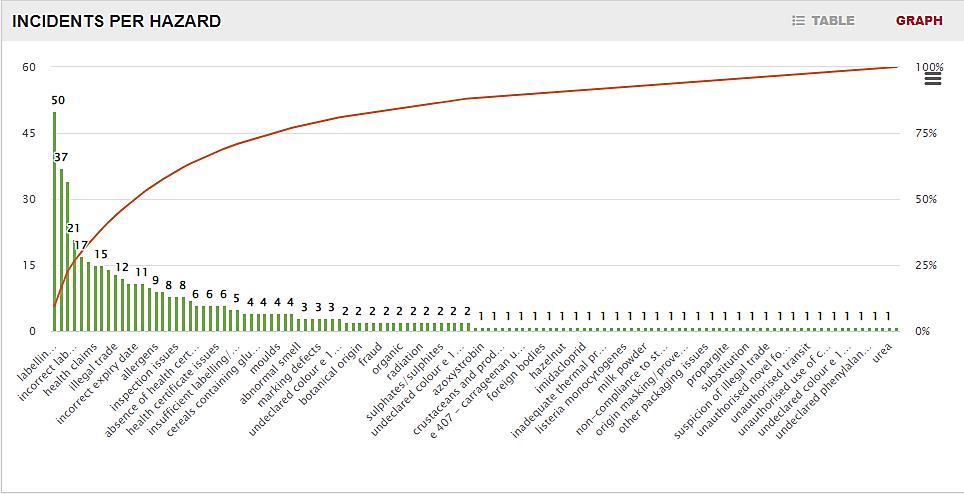

For 2023, food fraud incidents are up to 361, up until March. They are concerning frauds such as misdescription of labeling, smuggling, compositional deviation, or incorrect expiry date (Graph 2 by FOODAKAI).

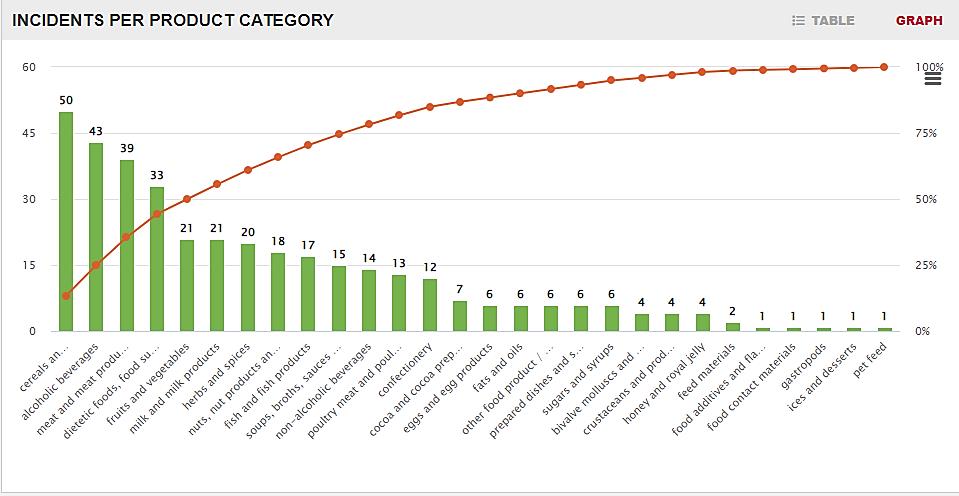

The US, France, Italy, Czech Republic, and India are the product countries with the most incidents. The product categories for these frauds are exhibited in the following Graph 3.

Up until March 2023, cereals and bakery products are the food category burdened with the most fraud incidents. Nevertheless, according to the data from the annual reports from the Agri-food Fraud Network of the EC, most EMA cases concern the following.

- Existence of toxic substances in the category of fruits and vegetables.

- Illegal treatments, primarily color-stabilizing treatments, of the category fish and products thereof.

- Artificial colorants/synthetic dyes in the category of cereals and bakery products

- Standards of non-compliances for the category fats and oils

- Falsified documentation for the categories meat and meat products and poultry and poultry meat products

A fraud issue, with huge magnitude, is the adulteration of alcoholic products, the second most burdened category as shown in Graph 1. According to the “Global status report on Alcohol and Health 2018” WHO, 25% of the alcohol consumed around the world is counterfeit. Most cases concern the addition of cheap methanol instead of ethanol, as a basic ingredient. Consumption of methanol may lead to severe illness or death upon intoxication (methanol poisoning). Thirty-seven people died and 7 were hospitalized between November 24th and December 20th, 2022 in Bogota after drinking liquor containing methanol. Thirteen people died last September in Morocco, due to poisoning from adulterated alcoholic beverages.

As far as wine frauds, mislabeling the varietal or growing area or blending in other varietals are the common adulteration practices. In 2002 in Bordeaux, France, large-scale producers were importing cheaper wine from other regions and selling it with the Bordeaux label. In 2008 and 2009, Italian officials declassified almost 2 million liters of high-value wine from five wineries because it was made with unauthorized grapes or fertilizers, and hydrochloric acid and sulfuric acid were added to them. The fake wine, beer, and spirits sector is estimated to cost only in the UK £600m annually, according to the Guardian.

Aside from these categories, another product that is frequently subjected to adulteration by sweeteners’ swapping, dilution, use of antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, and mislabeling, is honey. Due to its high value, it is often a target of EMA because of the strong economic incentives.

Think that 60% of honey used in the U.S. is coming from imports, while various factors have led to quality control vulnerabilities in the market, including decreased domestic production, the lack of a federal standard of identity, and insufficient trade policies. In an insightful article on Food Watch, we read that 46% of EU-imported honey is potentially fraudulent and often undetected. The Joint Research Centre laboratory tested 320 batches of honey and the adulterated batches were found to contain sugar syrups made from rice, wheat, or sugar beet, which are prohibited in the EU honey directive, for the protection of human health. The economic state for import companies seems to be extremely high, and so is the risk to the consumers’ health.

Food fraud continues to be a significant risk in the food industry, costing businesses an estimated $30 to $40 billion annually, worldwide, and it is not going to be eliminated anytime soon. As supply chains get longer, more global, and more complex, there will be ever more opportunities for food fraud to occur. Prof. Chris Elliot says in the New Food Magazine that small to medium size businesses (SMEs) are more vulnerable to food fraud; “On one side, there are large companies with good technical teams and budget for sampling and testing […]. They are not immune from fraud challenges but have put a large number of preventative measures in place […]. Compare this with SMEs, which have very limited technical resources and little or no testing programs in place […] many businesses will fall back on trusted business relationships and standard audits to protect themselves”. In fact, Saskia M. van Ruth et al. claim that casual dining operators are the most food fraud vulnerable group. According to their published study “Feeding Fiction: Fraud Vulnerability in the food service industry”, food service operators rated high vulnerability for 40% of the fraud indicators. This is considerably more than food manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers did previously. Mass caterers seemed the least vulnerable operators because they had more adequate food fraud controls in place. The fraud vulnerability was mostly determined by the type of food service operator rather than the type of food product. The good news is that there are approaches that could potentially limit EMA in the food industry, if not prevent it completely. Governments should establish strict regulations, enforcement measures to detect EMA, and surveillance programs to monitor the market.

Food companies must increase testing and monitoring of their products to detect any fraud. Transparency in the supply chain can, with the implementation of digital traceability systems and other innovative technologies, must be the condition sine qua non. The million-dollar question is, do the stakeholders want to collaborate and put an end to food fraud? Otherwise, maybe we should all take the “leap of faith” and convince ourselves that we are actually eating what we think we are eating.