Salmonella: A Pervasive Risk in the Food Chain

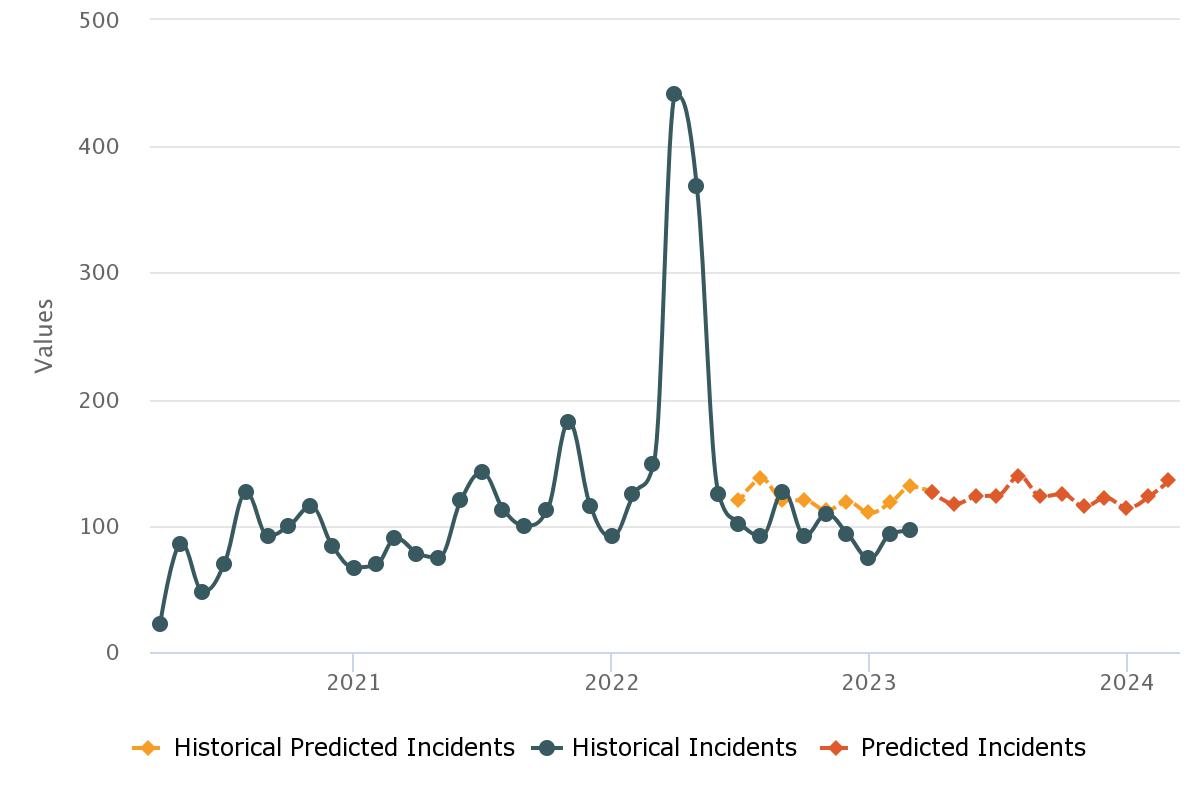

Salmonella is the most common foodborne bacteria and is a persistent threat to food safety. There have been numerous outbreaks and recalls in the past twelve months linked to the pathogen, and the impact of such incidents can be felt long after the event itself; just in February this year, French dairy group Lactalis was criminally charged in France over a case dating back to 2017, when 35 babies showed symptoms of salmonella within three days of consuming products by the company, mainly its infant formula. The incident resulted in 12 million boxes of powdered baby milk being recalled and affected around 83 countries. A more notable incident involves a treat popular worldwide, Ferrero, with the company making headlines as its salmonella-tainted products made their way to over 100 countries from a Belgian chocolate factory, its reputation suffering greatly as a result.

There are two species of the bacterium: S. Enterica and S. Bongori, with over 2,500 serotypes. The disease is most commonly caused by the former species, and in humans, most cases are caused by the S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium serotypes. However, there are several strains of the bacterium that can infect warm-blooded animals, such as S. Gallinarum in chicken and S. Choleraesuis in pigs. Many of these strains can also infect humans.

Contaminated water or food is the most common way humans become infected with salmonella, with an estimated 94% of salmonellosis transmitted this way. This makes the pathogen a major consideration for food safety, especially when the risks to human health are considered. Salmonellosis commonly causes gastroenteritis, or inflammation of the intestinal tract, which results in abdominal pain and severe diarrhea. The bacterium can also enter the blood, which is called bacteremia, while S. Typhimurium in particular can cause typhoid fever, a condition that can be life-threatening and requires antibiotic treatment. In the United States alone, more than 1 million people fall ill from salmonella, 26,500 need to be hospitalized, and around 400 die from the disease each year, according to the CDC. The disease is one of the four key global causes of diarrhoeal diseases, as per the World Health Organization.

Salmonellosis can occur when foods contaminated with feces from an infected animal are consumed, and therefore many cases can be traced back to foods of animal origin such as beef, poultry, milk, and eggs. However, any food can become contaminated via cross-contamination, through the environment or during handling by workers across the supply chain. Naturally, direct contact with infected animals like chickens and even turtles and iguanas can also transmit the bacterium. Salmonella has caused outbreaks in a wide variety of food products, including fresh sprouts, peanut butter, and chocolate, but also fresh produce such as alfalfa sprouts, baby spinach, basil, cantaloupe, lettuce, peppers, and tomatoes.

Because salmonella is very resistant and can survive for several weeks in a dry environment and several months in water, it can be introduced to foodstuffs during any stage of the supply chain, from agricultural production to the preparation of foods at home and in restaurants. Salmonella's ability to form complex surface-associated communities, or biofilms, enhances its persistence in various environments, including food processing settings. These biofilms are influenced by different environmental signals and adapt to a range of environments to protect the bacteria against stress factors such as desiccation, disinfectants, and antibiotics. Biofilms formed by Salmonella pose a significant challenge to food safety, as they can develop on many surfaces such as plastic, metal, glass, wood, or even on the food itself. In food-related industries, surfaces and equipment are frequently populated by microorganisms forming biofilms, which can increase microbial loads on intermediary and final products, reducing shelf life, and serving as a source of cross-contamination.

To examine how Salmonella ends up in our food, we first need to look at the beginning of the food chain - agriculture. Salmonella occurs naturally in the digestive tracts of humans and animals but also lives naturally in the environment. Because it requires energy, moderate temperature, and moisture to develop, it is easy for the bacterium to find its way into feed and feed products. In farming environments, one study found that contaminated ingredients in the brood and pasture feed in US poultry farms were highly correlated with the presence of salmonella before and after harvesting. Moreover, as the number of years of operation increased, the probability of finding Salmonella also increased. In the EU, researchers found that pig sows were the main source of infection in pigs raised for meat production where the prevalence of the bacterium was over 10%, with feed being the main source of infection below this percentage. Of course, meat and animal products are not the only sources of salmonella infections: other studies showed that pig and poultry manure can sustain the bacterium for up to 21 days and one year, respectively, thereby infecting agricultural soil and colonizing plants through their interaction with it, either via their root system or by soil contaminating the leaves.

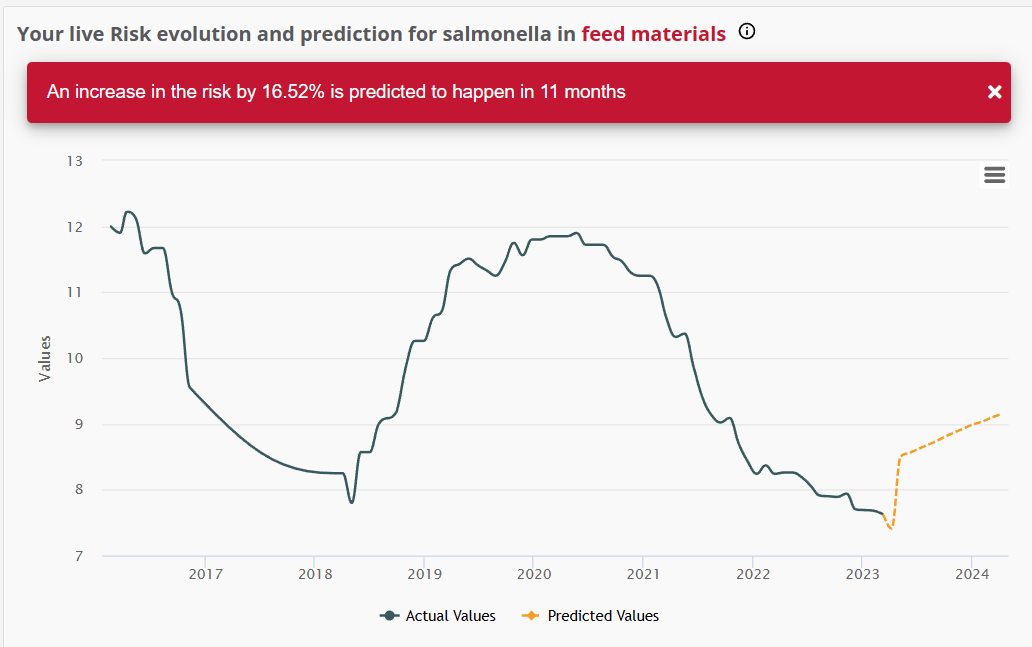

In fact, Salmonella could be even more prevalent than one would like to think, with estimates for its presence in finished feed and feed ingredients ranging from 3.2% to 12.5%. While the risks of infection are even higher for raw materials than finished feed and milling equipment, feed processing such as grinding and mixing of ingredients into feed formulations can further enable the bacterium’s growth, which not only finds ample surface area to develop and raises the volume of contaminated material being processed, but can also spread through dust produced in facilities and taking up residence within feed mills. This makes it easy to see the connection between infections and animals, as feed is arguably one of the most important if not the most important input in the production of poultry and other meats and animal products. Given that feed is transported from fields to mills and processing plants, then to mixers, silos, and feeders, the probability of salmonella infection rises exponentially, especially considering that the pathogens now have direct access to the animals’ gastrointestinal tract.

Aside from contaminated raw materials, salmonella infections can also be traced back to poor hygiene practices in facilities, contamination of other ingredients used in processing such as water used in cooling and rinsing operations, inadequate cooking and processing temperatures, or improper practices in storage and handling of food. Particularly with regards to water used as a vector for contamination, it is worth remembering that salmonella is frequently and naturally present in surface water and can find its way into food via irrigation. The bacterium can survive in aquatic environments via a number of mechanisms, which is important to keep in mind when evaluating the risks of infection. A variety of sources can produce salmonella-contaminated water, including agricultural runoff, sewage leaks, and stormwater runoff. It is also possible for water sources to become infected by salmonella after flooding or other natural disasters.

At the final end of the food chain, consumers are also susceptible to salmonella infections through various routes of exposure, either directly through contaminated food products or indirectly through cross-contamination. For example, fecal bacteria can be present in raw meat or in unwashed vegetables and fruit. Handling raw eggs and undercooking meat in particular increases the risk of salmonella infection. Another usually overlooked source of contamination in the kitchen is spice racks, as spice bottles are the item most likely to become contaminated after cooking. A 2022 study showed salmonella presence in around half of the spice containers after cooking poultry, given that many people neglect to wash their spice bottles and jars after they are done. Refrigerator handles, trash can lids, and cutting boards are also common surfaces harboring bacteria.

Companies use a number of methods to prevent salmonella infections. Food processing techniques that use a thermal treatment such as grilling are considered to be among the most effective for eliminating both salmonella and other foodborne pathogens, although some strains can grow at temperatures as high as 54 °C. There are also a number of non-thermal preservation methods, including chemical, physical, and biological treatments such as high-pressure processing, pulsed electric fields, and ozone or ultraviolet light. On the consumer end, it is relatively easy to avoid contamination if proper food safety measures in food preparation and storage are followed, with particular attention paid to high-risk foods like raw or undercooked meat, poultry, and seafood.

Successfully controlling salmonella requires a holistic approach, with measures taken at the farming, processing, and consumer levels. Considering the prevalence of the bacterium and the potentially serious health side effects, a concerted effort to mitigate risks must be made across the entire food supply chain, from agricultural production to the preparation of food in homes and restaurants.